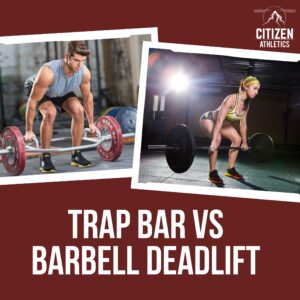

Today we’re going to take a brief look at some of the science behind the trap bar deadlift and discuss how it differs from the conventional barbell deadlift. But first, it might be interesting to discuss the origin of the trap bar deadlift.

The history of the trap bar

In the history of weightlifting, bodybuilding, and strongman, and training for sport, the trap bar is a relatively young and novel tool. It was designed by a powerlifter named Al Gerard in the mid 1980s as a tool to more comfortably train the squat and deadlift pattern.

Al spent his 20s and 30s working on a farm and was known for lifting 100 and 200 lb. bags of fertilizer as a means of training. Early in his lifting career, he observed significant transfer to his squat and deadlift numbers.

But as he got stronger, he reached a point where a 200 lb. bag of fertilizer wasn’t enough to help him improve his 450 lb. squat. However, he had learned there were other potential ways to get stronger in powerlifting besides only doing the primary lifts. Al was always experimenting.

In addition to lifting non-gym objects, Al used to hold heavy dumbbells at his sides and do a squat-deadlift hybrid movement. He did this because it felt better on his back than the traditional barbell lifts.

Now if you’ve ever tried this variation, you’d know that heavier weights and bigger dumbbells become awkward and challenging to hold. They bang into your knees and thighs, they’re pretty unstable, and they force you to maintain a narrow stance. Al was inspired to design the trap bar as a means to add heavier load to one of his favorite accessory movements.

What makes the trap bar so popular?

The trap bar allows you to keep your hands wider than you would be able to if you were holding two dumbbells, and also allows you to add significantly more load as it is plate loaded. Although the trap bar was originally designed as a replacement to the dumbbell squat, it has evolved into an easy-to-learn, low-back-friendly lift that is a staple in most serious weight rooms across the world.

According to our friends over at strongerbyscience.com, trap bars allow for greater flexibility in movement, higher velocity and power output, and are easier to learn for a lot of people.

For this reason, many people can deadlift a bit more with a trap bar. It can also be a preferred method of loading for a coach who has time constraints with their athletes and wants to spend more time lifting and less time teaching.

Many coaches have begun to favor the trap bar more because athletes find it to be more comfortable. The largest impediments to trap bar usage tends to be personal opinion and equipment accessibility rather than practicality. Peak moments and force at the low back are lower with the trap bar, and peak knee force tends to be higher.

Research shows the trap bar places less stress on the low back and more demand on the lower body, making it a potentially low back sparing movement that focuses more training on the powerful thigh muscles that are associated with sprinting, acceleration, and jumping.

Trap bars also typically have high and low handles, giving lifters two different range of motion options that are easy to use. With a simple flip of the bar, you can utilize two different height lifts. It’s much faster to use the high handles than it is to set up blocks or a power rack to decrease range of motion. In the team strength and conditioning world time is limited and convenience is highly coveted.

Basic Differences: Barbell vs Trap Bar vs Squat

The best way to understand the orthopedic and muscular demand differences between the trap bar deadlift, conventional deadlift, and squat, is to look at the studies that have measured hip:knee moment ratios.

A moment is a complex biomechanical and laboratory measurement that can be most easily understood by considering the total range of motion of the joint and the inertial force required to elicit movement.

For example, the largest knee moment in a squat is in the hole, and the largest hip moment in a deadlift is in the starting position- it’s where the joint and surrounding musculature need to work the hardest. Without diving too far into the research and collection methods, these three comparative hip:knee moment ratios below help to illustrate the difference between the three lifts.

Hip:knee moments

Conventional deadlift – 3.68:1

Trap bar – 1.78:1

Squat – .83:1

Numbers from strongerbyscience.com

What these numbers tell us is that the squat is the most quad or knee dominant, the conventional deadlift is the most hip dominant, and the trap bar sits right in between the two, but is still very much a hinge and hip dominant movement.

Studies have also shown the peak spinal and hip flexion moments of the conventional deadlift to be 9.2% and 8.4% higher compared to the trap bar deadlift, confirming the idea of it being low-back sparing.

The graphic below (from strongerbyscience.com) does a great job illustrating the continuum of primary lifts and the relative squat versus deadlift.

So which one is better?

The discussion of which lift is better is nuanced. One should consider individual preference, training goals, sport demands, and injury history. It is my hope that by explaining the differences between these lifts can help you to determine which one is better on a case-by-case basis.

The trap bar tends to settle into a person’s center of mass better, requires less teaching, allows for more movement freedom, elicits greater peak power production, reduces the likelihood of low back strain, and places more demand on the thighs. This does not make it better or worse, just simply different. Content is key!

If someone has knee pain, or a knee injury, a barbell deadlift or even RDL might be a great way to create a training effect without stressing the knees. Whereas if someone has a low back issue, the opposite might be true.

If someone is recovering from a hamstring injury and needs to spend more time strengthening their posterior chain, then a barbell deadlift might be a better option for them. The barbell deadlift is more challenging on the hips, glutes, and hamstrings than the trap bar. This can be a major advantage of the barbell in some scenarios.

If someone wants to train for powerlifting or weightlifting, it should be pretty obvious that training the lifts they are going to compete in should be their top priority, hence the reasoning behind spending less time with a trap bar and more time with a barbell. That being said, transfer can still be realized as long as intensity is sufficient and the primary lifts are trained enough to concurrently improve skill.

Case Study Example

If a 6’8, 17 year old basketball player with minimal training experience is doing a 10-week off-season lifting program, the trap bar deadlift might be the only primary compound bilateral lower body lift they need in order to maximize their potential and minimize injury risk, time spent teaching, and the weight room learning curve.

If that same basketball player is now 22, has had a history of knee injury, has never had a low back issue, and is in season, a barbell deadlift from blocks or an RDL might be a better option.

Now if that player is now 28, still playing basketball, and has had a few good years of minimal knee pain, but is experiencing low back pain, they might go back to the trap bar.

Conclusion

In the world of lifting and strength training people will always have strong opinions. Some prefer the straight barbell for themselves, as they’ve had great results with it and enjoy the nuances of the conventional deadlift form, myself included.

Others prefer the trap bar, as they argue it’s safer and easier. Regardless of the argument, it should be understood that optimal lifts and individualization is a moving target: all factors must be considered to decide what lift is most appropriate at what time.