As health-conscious individuals, we all know that resistance training is an important aspect of health, longevity and athletic performance. But, the rise of terminology perfectionists has led to apparent confusion and misinterpretation of basic elements in resistance training.

Let’s kick things off with a quote, shall we?

“There is no greater impediment to the advancement of knowledge than the ambiguity of words.”

Thomas Reid

The words we use are important, but when those same words create confusion & misunderstandings about simple concepts, we need to look at ourselves and understand why we adopt the language we use.

WHAT IS STRENGTH?

Recently, the term ‘Strength’ has received a lot of negative attention due to some individual’s misinterpretation of what strength truly means. You may ask yourself, ‘How the hell can strength as a term get negative attention?! Who’s so particular that they won’t just use a generic term??’ and if you are asking yourself that, let me tell you – you’re reading my mind.

Clinicians and coaches have opted to use ‘force’ as a more literal use of the word ‘strength’ when discussing resistance training, or other athletic activities. It’s true, force is the ‘actual measure’ that people are assessing with many tests, however there are limitations to omitting the term ‘strength’ from someone’s vocabulary. Now, before I say my piece, let me just say that this approach is accurate and has merit when assessing the force output that a limb exerts on some gauge measuring literal force (aka – Newtons). Some may want this discussion to be a Physics deep dive where we discuss levers, moments, torques, and how those variables interact. I hate to disappoint, but my scatter brain is only capable of addressing one topic at a time. Maybe a later post will discuss other physical nuances.

In the context of a normal training setting, I still tend to use the term ‘strength,’ here’s why:

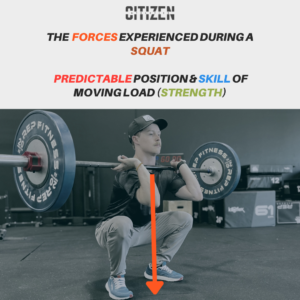

When we’re talking about ‘strength,’ it should be understood that we’re talking about a term that is ‘task-specific.’ There is no such thing as just being ‘strong.’ Being ‘strong’ means that you’re strong in a specific context – ie a squat, a jump, a swing, etc. This strength is based on your experience and individual muscle capacities/contributions to that movement. Let’s apply a more tangible example so that we can really sink our teeth into these concepts.

Squats are a perfect example of how I would differentiate ‘force’ and ‘strength.’ For example, while related, and often correlated, knee extension force production and squat strength don’t always line up. This means two individuals may have the exact same knee extension force production, but different 1RM squat numbers. This is often due to other variables like sport participation, squat familiarity, measurement differences with ‘force’ testing, and many others. Squats aren’t just determined by a single variable like ‘force,’ they’re underpinned by positions, actions, sequences and many other variables that make it difficult to apply the word ‘force’ to such a complex topic.

We are not just comparing apples to apples when we assess ‘force’ and ‘strength.’ There are nuances and characteristics that comprise what makes an individual ‘strong’ in a task, and while force is often a primary role-player, it takes a team of factors to improve someone’s ‘strength.’

LETS MUDDY THE WATERS EVEN MORE:

As we reflect on strength and its benchmarks, an important question arises: Strong enough for what activity? As we addressed, strength, as a quality, isn’t one-size-fits-all. It varies based on the activity or sport you’re engaged in. So, let’s put some tangible examples to these seemingly theoretical concepts.

POWERLIFTER: MAXIMIZING ABSOLUTE STRENGTH

A powerlifter’s primary goal is to lift as much weight as possible in the squat, bench press, and deadlift. For them, achieving high relative strength (strength per bodyweight) in these specific lifts is crucial. Their training, nutrition, and recovery are all structured around maximizing performance in these three exercises.

For a powerlifter, the “arbitrary” strength benchmarks like squatting 2x bodyweight, aren’t so arbitrary anymore, there is a much clearer context. Once the task becomes the actual sport itself, an athlete’s mentality will shifts from ‘how can I use this for my benefit’ to ‘how can I move the most weight possible.’ Said differently: their goal shifts from improving force, to maximizing their task-specific strength

As an athlete, you are training to maximize your sport performance given your current capacities. In doing so, there may be technique changes that allow you to lift MORE weight with the same amount of individual muscle force production. You begin ‘training for the test,’ and in doing so, likely will develop a technique that produces the most strength per unit of (individual muscle) force.

This is not to say that ‘training for the test’ won’t also improve innate force production. It certainly will. Instead, it is to provide an example that while saying ‘squat force production’ may not be incorrect, in a powerlifting context, it implies that force production, regardless of positioning, timing, or sequencing of an activity, is the operative component in the task.

In reality, the primary factor of somebody’s performance in the squat, bench, deadlift, or other sport-specific exercise (ie – Snatch) will be person-dependent. Most likely, it is some type of combination of force production, positioning, and timing that comprise task strength.

Still following? Good. Let’s bring a different example into the mix!

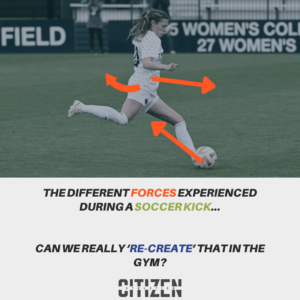

SOCCER CASE EXAMPLE: TRANSLATING FORCE TO PERFORMANCE

A soccer player’s primary goal isn’t to maximize how much they can squat or bench press. Instead, they use strength training as a means to improve on-field performance, reduce the risk of injury, and enhance their overall athleticism.

Resistance training is a means to an end. Squatting 2x bodyweight doesn’t magically mean you score more goals, make better passes, or even jump higher for headers. In these settings, strength training means you’re becoming more tolerant and capable of movements with high FORCES.

While it makes sense to explain that highly skilled movements require force, timing and sequencing just like the components of squat strength, I’ll shock the crowd and say that I’d be more inclined to adopt the term ‘force production’ over ‘strength’ with a soccer athlete. Here’s why:

Sport is chaotic. Sure, you can generally be confident of certain aspects of these activities: the opposing team will try to score in your goal, you’ll try to prevent it while also trying to score in theirs, and if there’s a big enough crowd, some dude will approach their mid-life crisis by dropping their trousers and sprinting across the field. Isn’t soccer the best?!

The sporting environment is unpredictable at best (& in more ways than one 😉). The same play will never happen twice, and even if you think plays, sprints or strikes feel the same as they did prior, we’re always changing our behavior based on the environment we surround ourselves in.

So… if the ‘test’ is always changing, how do we train for the test?

That’s the trick! You don’t.

By using resistance exercise as a way to improve the tolerance and capacity of your body’s tissues, you’re able to leverage your body’s ability to produce & tolerate force regardless of the position, task, or environment you’re placed in. Rather than seeing resistance training as a skill, we see it as a way to improve our armor, protecting us on the ever-changing battlefield.

LETS BRING THIS HOME

‘Force’ isn’t a wrong term to use; but neither is ‘Strength.’

When we start to visualize and understand the components that make up the tasks we set out to improve, we can appreciate that there is room for many descriptors in the movement science world.

As a synopsis, here is your ‘Too Long, Didn’t Read’ conclusion for today’s oddly-specific blog:

- Strength is underpinned by force, timing, sequencing and many other factors; if the exercises that you track are based on those factors, and measured by the external resistance & movement quality of the task, it’s likely best to call it strength (Bonus points if that task is literally the thing you’re competing in – ie: Powerlifting, Weightlifting, Strongman, CrossFit etc.)

- Force is a single variable; measurable with gauges, plates, dynamometers and other tech. If you are using those technologies as a means to measure a performance output that may have carryover to someone’s sport; it’s likely that you’re concerned with force.

Cohabitation is a beautiful thing… I’m all for specificity, semantics & updating our models in the name of being less wrong, but we often adopt new ideas like we jump into new relationships… head first. Broadly replacing ‘strength’ with ‘force’ doesn’t make you any better of a practitioner, but being able to conceptualize the two might…

Here’s something I try to ask myself whenever I start adopting a new thought, strategy or concept into my model:

Does changing, correcting, or modifying this *thing* actually move the needle for me as a coach, individual or practitioner?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dylan Carmody is a Doctor of Physical Therapy, and Strength & Conditioning Coach with 5+ years in the performance and rehab industries.

Having dabbled in training modalities like Olympic Lifting, Cycling, Powerlifting, and CrossFit, Dylan has a deep appreciationfor all things performance, while still having a positive and fun-loving approach to exercise.

Dylan’s coaching experience is equally eclectic, ranging from performance coaching for elite athletes in the NCAA D1 setting, to group fitness and weight loss coaching in his early career.

With detailed exercise programming & consistent communication, he aims to create a training environment that is not only ‘tolerable’ for clients’ aches and pains, but truly helps to resolve their issues in the first place.