The squat is a linchpin in the realm of fitness & performance; it has consistently been used as the universal display of lower body strength and power. Loved by many, feared by few, but respected by all, the squat sits atop the throne of exercise selection for it’s fundamental carryover to fitness, athletics, and general health. In this article, we dive deep into the scientific facets of this foundational exercise, exploring relative muscular contributions, determinants of squat performance, and how relative placement of loads and positions can help to optimize your performance and eventually meet the goals that we all have: improving our ability to sit down and stand back up with heavier weights.

It doesn’t take a rocket surgeon (you heard me) to realize that the squat is a highly variable movement. Not only do individual characteristics like limb length and joint range of motion dictate the differences in squats between individuals, but even expert movers as a whole don’t have the same two movements (google ‘Bernstein’s Hammer’ and see what you get!). Squats are just like you and me, individual little snowflakes

While nuance is often lost in arguments about lever arms and torso angles that occupy instagram comment sections, reddit threads, and dinner time conversations (Really? Just me?), we are on the path to discovering that nuance once and for all. So buckle up Citizen Athletics team, because you’re about to get LEARNT UP today!

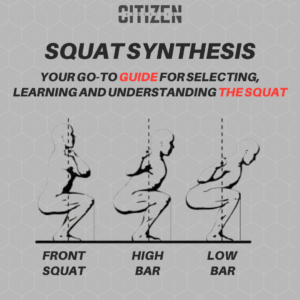

Squat Variants and Which YOU Should Pick

The 3 most frequent squat variations that many implement are dictated by the relative bar position in relation to the person’s center of mass. The basics of biomechanics will dictate that where we place the load on our body is going to determine the relative muscle contributions and rate-limiters to the exercise. So lets dive into what that fancy science-jargon really means:

Low Bar Back Squat

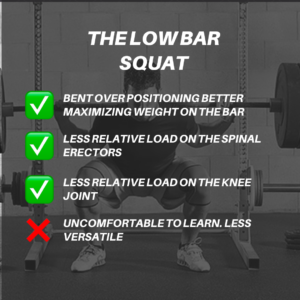

The Low Bar Back Squat is most often the ‘weapon of choice’ for athletes that are looking to move as much weight as humanly possible. Colloquially termed ‘The Big Uglies,’ strength athletes like Strongmen, Powerlifters and athletes that require high levels of force production like Track & Field Throwers & Football Linemen often choose this squat variant.

But why? Is there some secret society with a blood-pact that they all were sworn to secrecy about their choice of squat patterns? Maybe. Or… Maybe it’s due to the relative barbell position.

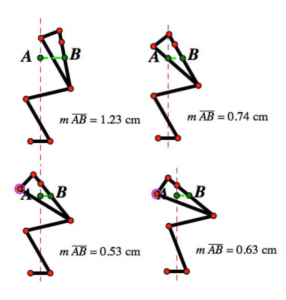

When all other factors are kept equal, the low bar back squat allows athletes to lift heavier weights, and the results are not insignificant. Often there is a 5-10% difference in weight tolerated between the high bar and the low bar back squat. This difference is generally attributed to the force that the athletes’ back extensors have to overcome between ‘Low Bar’ and ‘High Bar.’ The photo we have attached can help tell the story.

As you can see on the highly sophisticated stick figures on the right, the intersection of the red dotted line and the upper trunk of the figure represents the position of the barbell on the athlete’s body. The green dot labeled ‘B’ is the location of many of the common muscular insertions on the spine, these are the muscles that have to counteract the force of the barbell pushing down on our back. The further away ‘B’ is from the dotted line, means that there is more and more effort that those spinal erector muscles have to work to keep the body upright.

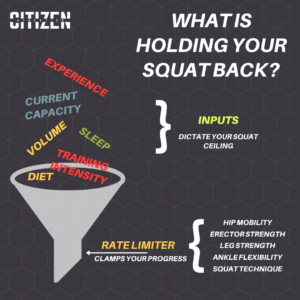

This brings up a great vocab word: Rate Limiters. Rate Limiters are bottlenecks in a task – you know… ‘the weakest link.’ What many don’t realize about the squat is that the most limiting factor often isn’t your legs… it’s your back. BUT, by squatting with a Low Bar Position we are closing the gap between ‘B’ and the dotted line, therefore reducing the amount that the spinal erectors have to work. With the low bar squat, we get to open the flood gates and see what those tree trunks are really made of!

While great for force production and transmission, this squat variation places increased demands on hip mobility due to the forward flexed trunk position. These demands are neither good nor bad, they are just part of the determinants that may encourage you to choose one squat pattern over the other.

The High Bar Back Squat

The High Bar Back Squat is likely the most common squat variation on the market today. Simply put, you find the meatiest part of your traps and shove the bar there. The higher bar position on the back also increases the horizontal distance between load and back extensor muscles, which places a greater relative demand on the spinal erectors. This increased demand, along with potential changes in lower extremity force distribution, is often the Rate Limiter in performance, restricting the total load someone can put on the bar.

So, why would anyone squat high bar? Don’t we all want to maximize performance?

Believe it or not, ‘performance’ is a relative term. Take the sport of Olympic Weightlifting for example. ‘Oly’ lifters would still be considered ‘strength athletes’ as they look to maximize the total amount of load on the bar during their lifts. But, they often select high bar back squats due to the relative carry over that they have in producing strength for tasks like the clean and snatch. So, how is that the case?

The positioning of the bar has a great deal of impact on the center of mass of the individual. During the squatting motion, the forces from the barbell that drive the hips down and knees forward will change based on where the barbell is placed. While the load is still the same, the high bar back squat tends to distribute load favoring the quadriceps when compared to the low bar back squat, which favors the load to be placed more so in the hips. This distribution ‘forward’ is also seen in the front squat (mimicking the clean) and overhead squat (mimicking the snatch) which makes the carryover between these movements much more similar than the low bar back squat.

While it may appear that the high bar back squat has emerged as your new ‘front running contender’ for the People’s Choice Awards, it is important to discuss the mobility demands of this variant. While there is less demand on the hips, there is a greater focus on mobility demands through the ankle with this variation, due to the need of our knees to track forward. Ugh, give and take is a constant.

The Front Squat:

As you may be able to rationalize now, the front squat is going to have the greatest demand placed on the spinal extensors, due to the increased distance that the bar is placed away from the back. Therefore, there will be a large bottle neck (aka Rate Limiter) in one’s capacity to move a large amount of load in this squatting pattern.

This limitation is so large that some individuals, when familiarity and experience is equal between patterns, may still only be able to front squat 80% of their best high bar back squat. However, as noted previously, this pattern will also likely distribute relative loads forward (aka towards the quadriceps) which can create an advantageous stimulus for those who are looking to improve their quadriceps strength, or look for better carryover into the Olympic Lifts. Not to mention, the greater demand that front squats place on the spinal extensors also makes them a great strengthening exercise for the spinal extensors themselves. Which could in turn help to improve one’s back squat strength by mitigating the relative Rate Limiter in performance.

So… Which Should I Train?

Great question! Here’s the diplomatic answer many of you were expecting.

When you add up the demands of the knee extensors (quads) and hip extensors (glutes and hamstrings) for all 3 squat variants (when load is equated), the SUM is the same. So… What does that really mean? Essentially, load is load. Wherever you place the bar isn’t going to change the amount of load on the system, but rather, the relative contributions that your muscles are providing. So, squat in a manner that is reflective of the goals you set for yourself.

Want me to get even MORE diplomatic? Done. Despite mechanical differences in each pattern, studies show minimal differences in muscle activation and training effects between the squat variants, with no one squat clearly superior in yielding strength or mass gains.

If you are someone who wants to train to maximize the sheer number of pounds (or kgs, stones, etc.) on the bar (in a squat), it’s likely that you’ll find the most success with the low bar back squat. However, if you are looking for the squat to have carry-over to a specific task – then you should probably find out what that task asks of the legs, and then try to match the specific squat pattern to those demands.

Note – as we mentioned in the front squat section, you may want variability in your squatting stimulus to emphasize certain performance enhancing qualities. For example, an ‘Oly’ lifter may replace Front Squats with Low Bar Back Squats in a training block during the off-season to maximize the load placed in the legs and reduce the relative intensity of load through the spinal erectors. This may be helpful to elicit a new adaptation, however, it is important to factor in the ‘skill’ of squatting. When competitions are looming, it is likely best for the athlete to practice the movement that most closely represents their competitive task.

DETERMINANTS OF SQUAT PERFORMANCE

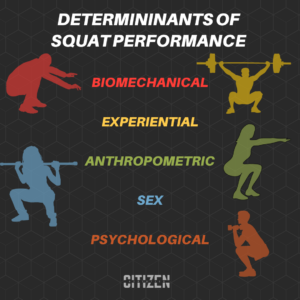

Oh boy. While there are a multitude of determinants for the squatting pattern that have been measured, such as Biomechanical, Anthropometric, Experiential, Sex, and Psychological characteristics, this section will largely focus on the immediately modifiable characteristics based on a constraints-based approach. That’s right. It’s Biomechanics time.

While certain ‘best’ techniques are presented on the internet with little evidence or simply ‘expert opinion’ disguised as an authoritative figure (ie – ‘___ University,’ ‘___ Institute,’ you get the point), we hold ourselves to a higher standard at Citizen Athletics.

Let’s begin by stating that we see ‘optimal’ as the positions, speeds and accessible ranges that allow you to lift the most weight with the least relative amount of force. This means we are looking for the positions and joint angles that will allow the most people to squat the most amount of weight possible. Based on biomechanical modeling, an ‘optimal’ technique tends to bias load favoring the hips over the knees. This is likely due to the fact that 3 out of the 4 main contributing muscle groups of the squat (Glutes, Erectors, Hamstrings) attach at, or affect the hips in some way, whereas the knee is left with the quadriceps as the sole prime movers, while the hamstrings may play a stabilization-type role.

Something important to note in most high load lifts, there are going to be ‘failure points’ for certain muscle groups during the lift. Said differently, we’re trying to get the most juice out of each muscle group before jumping ship and loading the ‘next in line.’ But, what does that effectively mean in execution?

This has to start by acknowledging that we were wrong… Okay fine, I was wrong. You know how I said that the spinal erectors are likely the biggest rate limiter or ‘failure point’ in the squat? Yeah, well there’s more nuance to that equation. What I should have said, is that the erectors are often the last in line that take the brunt of the work once all other groups fail. So technically, yes, the back was the reason you failed the lift, but if your legs were stronger, your back wouldn’t have to deal with as much load to begin with.

BUT – instead of trying to never let any of these muscle groups ‘fail.’ Why don’t we use their failure to our advantage? Let’s unpack this:

You know how I said that ‘optimal’ tends to bias the hips more than knees right? Well, that is generally because the quads are the first to ‘irish goodbye’ to the squat party. Based on research studying the electrical muscle activity during squatting, the glutes effectively are just used as passive support in the bottom of the squat. If you’re squatting below parallel, you’re likely to be placing the glutes under an insane amount of stretch, which is quite ‘sub-optimal’ from a strength perspective. So what should we do to ‘get out of the hole?’

Well shit, if the quads are the first to leave, let’s squeeze ’em for all the juice they’ve got! Driving out of the hole with your knees shoved forward will let you use the muscles that are primed to work in that position, and once they fail, guess what? Your body will shift backwards to shield the load away from the quads and into the hips! Your body knows the quads aren’t getting you out of this mess, and if you want to leave the gym alive, your hips are going to have to take over. Adopting this strategy allows us to leverage two sub-optimal performance requirements (glute length and quad strength) to get stoned with two birds… or… uhh… nevermind.

One last concept before this paper bores you to sleep – let’s talk about speed and timing. When squatting to maximize the weight on the bar (rather than maximize muscle growth), the speed that you sink into the squat is imperative. While there is evidence showing that quicker squat descents will lead to greater peak force and power production, there is a level of diminishing returns with this concept. Having a controlled descent is important to ensure that you’re able to assume the positions necessary to maximize total load on the bar.

Squatting with a smooth, brisk descent will likely allow you to maximize the total load on the bar. By not spending excessive time on the eccentric (downward) phase, you’re minimizing the amount of work your legs are having to counteract, saving your limited muscle energy for the concentric (upward) phase that is inherently more difficult.

So there you have it, folks! We wish we could market this as ‘the ultimate squat guide’ or ‘the only article you’ll ever need for squatting,’ but last time we checked, there are like a thousand of those. So instead, we hope that this was ‘just another squat article’ that gave you a few helpful pearls, or refreshed you on some concepts that you may have already been familiar with. After all, ‘The Only Thing You’ll Ever Need’ to learn more about squatting is right here:

https://www.instagram.com/reel/Cs8iHeTJCtk/?igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dylan Carmody is a Doctor of Physical Therapy, and Strength & Conditioning Coach with 5+ years in the performance and rehab industries.

Having dabbled in training modalities like Olympic Lifting, Cycling, Powerlifting, and CrossFit, Dylan has a deep appreciationfor all things performance, while still having a positive and fun-loving approach to exercise.

Dylan’s coaching experience is equally eclectic, ranging from performance coaching for elite athletes in the NCAA D1 setting, to group fitness and weight loss coaching in his early career.

With detailed exercise programming & consistent communication, he aims to create a training environment that is not only ‘tolerable’ for clients’ aches and pains, but truly helps to resolve their issues in the first place.

Sources:

- Aspe, Rodrigo R., and Paul A. Swinton. “Electromyographic and Kinetic Comparison of the Back Squat and Overhead Squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 28, no. 10, 2014, pp. 2827-36, doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000462.

- Barrett, Kiara B., et al. “A Comparison of Squat Depth and Sex on Knee Kinematics and Muscle Activation.” Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, vol. 145, no. 7, 2023, doi:10.1115/1.4062330.

- Bloomquist, K., et al. “Effect of Range of Motion in Heavy Load Squatting on Muscle and Tendon Adaptations.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 113, no. 8, 2013, pp. 2133-42, doi:10.1007/s00421-013-2642-7.

- Braidot, A. A., et al. “J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 90 012009.” J. Phys.: Conf. Ser., vol. 90, 2007, doi:10.1088/1742-6596/90/1/012009.

- Bryanton, Megan A., et al. “Quadriceps Effort during Squat Exercise Depends on Hip Extensor Muscle Strategy.” Sports Biomechanics, vol. 14, no. 1, 2015, pp. 122-38, doi:10.1080/14763141.2015.1024716.

- Clark, Dave R., et al. “Muscle Activation in the Loaded Free Barbell Squat: A Brief Review.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 26, no. 4, 2012, pp. 1169-78, doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822d533d.

- Coratella, Giuseppe, et al. “The Activation of Gluteal, Thigh, and Lower Back Muscles in Different Squat Variations Performed by Competitive Bodybuilders: Implications for Resistance Training.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 2, 2021, p. 772, doi:10.3390/ijerph18020772.

- Marchetti, Paulo Henrique, et al. “Muscle Activation Differs between Three Different Knee Joint-Angle Positions during a Maximal Isometric Back Squat Exercise.” Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 2016, 2016, doi:10.1155/2016/3846123.

- McBride, Jeffrey M., et al. “Comparison of Kinetic Variables and Muscle Activity during a Squat vs. a Box Squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 24, no. 12, 2010, pp. 3195-9, doi:10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181f6399a.

- McKean, Mark, and Brendan J. Burkett. “Does Segment Length Influence the Hip, Knee, and Ankle Coordination during the Squat Movement?.” Journal of Fitness Research, vol. 1, no. 1, 2012, pp. 23-30.

- Paoli, Antonio, Giuseppe Marcolin, and Nicola Petrone. “The Effect of Stance Width on the Electromyographical Activity of Eight Superficial Thigh Muscles During Back Squat with Different Bar Loads.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, vol. 23, no. 1, 2009, pp. 246-250.

- Park, Ju-Hyung, et al. “Influence of Loads and Loading Position on the Muscle Activity of the Trunk and Lower Extremity during Squat Exercise.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 20, 2022, p. 13480, doi:10.3390/ijerph192013480.

- Schoenfeld, Brad J. “Squatting Kinematics and Kinetics and Their Application to Exercise Performance.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 24, no. 12, 2010, pp. 3497-506, doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bac2d7.

- Slater, Lindsay V., and Joseph M. Hart. “Muscle Activation Patterns During Different Squat Techniques.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 31, no. 3, 2017, pp. 667-676, doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001323.

- Sugisaki, Norihide, et al. “Difference in the Recruitment of Hip and Knee Muscles between Back Squat and Plyometric Squat Jump.” PloS One, vol. 9, no. 6, 2014, e101203, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101203.

- Van den Tillaar, Roland. “Effect of Descent Velocity upon Muscle Activation and Performance in Two-Legged Free Weight Back Squats.” Sports, vol. 7, no. 1, 2019, p. 15, doi:10.3390/sports7010015.

- Vigotsky, Andrew D., et al. “Biomechanical, Anthropometric, and Psychological Determinants of Barbell Back Squat Strength.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 33, Suppl 1, 2019, pp. S26-S35, doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002535.